Reading Passage 1

Manatees

Manatees, also known as sea cows, are aquatic mammals that belong to a group of animals called Sirenia. This group also contains dugongs. Dugongs and manatees look quite alike – they are similar in size, colour and shape, and both have flexible flippers for forelimbs. However, the manatee has a broad, rounded tail, whereas the dugong’s is fluked, like that of a whale. There are three species of manatees: the West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus), the African manatee (Trichechus senegalensis) and the Amazonian manatee (Trichechus inunguis).

Unlike most mammals, manatees have only six bones in their neck – most others, including humans and giraffes, have seven. This short neck allows a manatee to move its head up and down, but not side to side. To see something on its left or its right, a manatee must turn its entire body, steering with its flippers. Manatees have pectoral flippers but no back limbs, only a tail for propulsion. They do have pelvic bones, however – a leftover from their evolution from a four-legged to a fully aquatic animal. Manatees share some visual similarities to elephants. Like elephants, manatees have thick, wrinkled skin. They also have some hairs covering their bodies which help them sense vibrations in the water around them.

Seagrasses and other marine plants make up most of a manatee’s diet. Manatees spend about eight hours each day grazing and uprooting plants. They eat up to 15% of their weight in food each day. African manatees are omnivorous – studies have shown that molluscs and fish make up a small part of their diets. West Indian and Amazonian manatees are both herbivores.

Manatees’ teeth are all molars – flat, rounded teeth for grinding food. Due to manatees’ abrasive aquatic plant diet, these teeth get worn down and they eventually fall out, so they continually grow new teeth that get pushed forward to replace the ones they lose. Instead of having incisors to grasp their food, manatees have lips which function like a pair of hands to help tear food away from the seafloor.

Manatees are fully aquatic, but as mammals, they need to come up to the surface to breathe. When awake, they typically surface every two to four minutes, but they can hold their breath for much longer. Adult manatees sleep underwater for 10–12 hours a day, but they come up for air every 15–20 minutes. Active manatees need to breathe more frequently. It’s thought that manatees use their muscular diaphragm and breathing to adjust their buoyancy. They may use diaphragm contractions to compress and store gas in folds in their large intestine to help them float.

The West Indian manatee reaches about 3.5 metres long and weighs on average around 500 kilograms. It moves between fresh water and salt water, taking advantage of coastal mangroves and coral reefs, rivers, lakes and inland lagoons. There are two subspecies of West Indian manatee: the Antillean manatee is found in waters from the Bahamas to Brazil, whereas the Florida manatee is found in US waters, although some individuals have been recorded in the Bahamas. In winter, the Florida manatee is typically restricted to Florida. When the ambient water temperature drops below 20°C, it takes refuge in naturally and artificially warmed water, such as at the warm-water outfalls from powerplants.

The African manatee is also about 3.5 metres long and found in the sea along the west coast of Africa, from Mauritania down to Angola. The species also makes use of rivers, with the mammals seen in landlocked countries such as Mali and Niger.

The Amazonian manatee is the smallest species, though it is still a big animal. It grows to about 2.5 metres long and 350 kilograms. Amazonian manatees favour calm, shallow waters that are above 23°C. This species is found in fresh water in the Amazon Basin in Brazil, as well as in Colombia, Ecuador and Peru.

All three manatee species are endangered or at a heightened risk of extinction. The African manatee and Amazonian manatee are both listed as Vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is estimated that 140,000 Amazonian manatees were killed between 1935 and 1954 for their meat, fat and skin, with the latter used to make leather. In more recent years, African manatee decline has been tied to incidental capture in fishing nets and hunting. Manatee hunting is now illegal in every country the African species is found in.

The two subspecies of West Indian manatee are listed as Endangered by the IUCN. Both are also expected to undergo a decline of 20% over the next 40 years. A review of almost 1,800 cases of entanglement in fishing nets and of plastic consumption among marine mammals in US waters from 2009 to 2020 found that at least 700 cases involved manatees. The chief cause of death in Florida manatees is boat strikes. However, laws in certain parts of Florida now limit boat speeds during winter, allowing slow-moving manatees more time to respond.

Reading Passage 2

Procrastination

A psychologist explains why we put off important tasks and how we can break this habit

A

Procrastination is the habit of delaying a necessary task, usually by focusing on less urgent, more enjoyable, and easier activities instead. We all do it from time to time. We might be composing a message to a friend who we have to let down, or putting together an important report for college or work; we’re doing our best to avoid doing the job at hand, but deep down we know that we should just be getting on with it. Unfortunately, berating ourselves won’t stop us procrastinating again. In fact, it’s one of the worst things we can do. This matters because, as my research shows, procrastination doesn’t just waste time, but is actually linked to other problems, too.

B

Contrary to popular belief, procrastination is not due to laziness or poor time management. Scientific studies suggest procrastination is, in fact, caused by poor mood management. This makes sense if we consider that people are more likely to put off starting or completing tasks that they are really not keen to do. If just thinking about the task threatens our sense of self-worth or makes us anxious, we will be more likely to put it off. Research involving brain imaging has found that areas of the brain linked to detection of threats and emotion regulation are actually different in people who chronically procrastinate compared to those who don’t procrastinate frequently.

C

Tasks that are emotionally loaded or difficult, such as preparing for exams, are prime candidates for procrastination. People with low self-esteem are more likely to procrastinate. Another group of people who tend to procrastinate are perfectionists, who worry their work will be judged harshly by others. We know that if we don’t finish that report or complete those home repairs, then what we did can’t be evaluated. When we avoid such tasks, we also avoid the negative emotions associated with them. This is rewarding, and it conditions us to use procrastination to repair our mood. If we engage in more enjoyable tasks instead, we get another mood boost. In the long run, however, procrastination isn’t an effective way of managing emotions. The ‘mood repair’ we experience is temporary. Afterwards, people tend to be left with a sense of guilt that not only increases their negative mood, but also reinforces their tendency to procrastinate.

D

So why is this such a problem? When most people think of the costs of procrastination, they think of the toll on productivity. For example, studies have shown that procrastination negatively impacts on student performance. But putting off reading textbooks and writing essays may affect other areas of students’ lives. In one study of over 3,000 German students over a six-month period, those who reported procrastinating over their university work were also more likely to engage in study-related misconduct, such as cheating and plagiarism. But the behaviour that procrastination was most closely linked with was using fraudulent excuses to get deadline extensions. Other research shows that employees on average spend almost a quarter of their workday procrastinating, and again this is linked with negative outcomes. In fact, in one US survey of over 22,000 employees, participants who said they regularly procrastinated had less annual income and less employment stability. For every one-point increase on a measure of chronic procrastination, annual income decreased by US$15,000.

E

Procrastination also correlates with serious health and well-being problems. A tendency to procrastinate is linked to poor mental health, including higher levels of depression and anxiety. Across numerous studies, I’ve found people who regularly procrastinate report a greater number of health issues, such as headaches, flu and colds, and digestive issues. They also experience higher levels of stress and poor sleep quality. They are less likely to practise healthy behaviours, such as eating a healthy diet and regularly exercising, and use destructive coping strategies to manage their stress. In one study of over 700 people, I found people prone to procrastination had a 63% greater risk of poor heart health after accounting for other personality traits and demographics.

F

Finding better ways of managing our emotions is one route out of the vicious cycle of procrastination. An important first step is to manage our environment and how we view the task. There are a number of evidence-based strategies that can help us fend off distractions that can occupy our minds when we should be focusing on the thing we should be getting on with. For example, reminding ourselves about why the task is important and valuable can increase positive feelings towards it. Forgiving ourselves and feeling compassion when we procrastinate can help break the procrastination cycle. We should admit that we feel bad, but not be overly critical of ourselves. We should remind ourselves that we’re not the first person to procrastinate, nor the last. Doing this can take the edge off the negative feelings we have about ourselves when we procrastinate. This can all make it easier to get back on track.

Reading Passage 3

Invasion of the Robot Umpires

A few years ago, Fred DeJesus from Brooklyn, New York became the first umpire in a minor league baseball game to use something called the Automated Ball-Strike System (ABS), often referred to as the ‘robo-umpire’. Instead of making any judgments himself about a strike*, DeJesus had decisions fed to him through an earpiece, connected to a modified missile-tracking system. The contraption looked like a large black pizza box with one glowing green eye; it was mounted above the press stand.

Major League Baseball (MLB), who had commissioned the system, wanted human umpires to announce the calls, just as they would have done in the past. When the first pitch came in, a recorded voice told DeJesus it was a strike. Previously, calling a strike was a judgment call on the part of the umpire. Even if the batter does not hit the ball, a pitch that passes through the ‘strike zone’ (an imaginary zone about seventeen inches wide, stretching from the batter’s knees to the middle of his chest) is considered a strike. During that first game, when DeJesus announced calls, there was no heckling and no shouted disagreement. Nobody said a word.

For a hundred and fifty years or so, the strike zone has been the game’s animating force—countless arguments between a team’s manager and the umpire have taken place over its boundaries and whether a ball had crossed through it. The rules of play have evolved in various stages. Today, everyone knows that you may scream your disagreement in an umpire’s face, but you must never shout personal abuse at them or touch them. That’s a no-no. When the robo-umpires came, however, the arguments stopped.

During the first robo-umpire season, players complained about some strange calls. In response, MLB decided to tweak the dimensions of the zone, and the following year the consensus was that ABS is profoundly consistent. MLB says the device is near-perfect, precise to within fractions of an inch. “It’ll reduce controversy in the game, and be good for the game,” says Rob Manfred, who is Commissioner for MLB. But the question is whether controversy is worth reducing, or whether it is the sign of a human hand.

A human, at least, yells back. When I spoke with Frank Viola, a coach for a North Carolina team, he said that ABS works as designed, but that it was also unforgiving and pedantic, almost legalistic. “Manfred is a lawyer,” Viola noted. Some pitchers have complained that, compared to a human’s, the robot’s strike zone seems too precise. Viola was once a major-league player himself. When he was pitching, he explained, umpires rewarded skill. “Throw it where you aimed, and it would be a strike, even if it was an inch or two outside. There was a dialogue between pitcher and umpire.”

The executive tasked with running the experiment for MLB is Morgan Sword, who’s in charge of baseball operations. According to Sword, ABS was part of a larger project to make baseball more exciting since executives are terrified of losing younger fans, as has been the case with horse racing and boxing. He explains how they began the process by asking fans what version of baseball they found most exciting. The results showed that everyone wanted more action: more hits, more defense, more baserunning. This type of baseball essentially hasn’t existed since the 1960s, when the hundred-mile-an-hour fastball, which is difficult to hit and control, entered the game. It flattened the game into strikeouts, walks, and home runs—a type of play lacking much action.

Sword’s team brainstormed potential fixes. Any rule that existed, they talked about changing—from changing the bats to changing the geometry of the field. But while all of these were ruled out as potential fixes, ABS was seen as a perfect vehicle for change. According to Sword, once you get the technology right, you can load any strike zone you want into the system. “It might be a triangle, or a blob, or something shaped like Texas. Over time, as baseball evolves, ABS can allow the zone to change with it.”

“In the past twenty years, sports have moved away from judgment calls. Soccer has Video Assistant Referees (for offside decisions, for example). Tennis has Hawk-Eye (for line calls, for example). For almost a decade, baseball has used instant replay on the base paths. This is widely liked, even if the precision can sometimes cause problems. But these applications deal with something physical: bases, lines, goals. The boundaries of action are precise, delineated like the keys of a piano. This is not the case with ABS and the strike zone. Historically, a certain discretion has been appreciated.”

I decided to email Alva Noë, a professor at Berkeley University and a baseball fan, for his opinion. “Hardly a day goes by that I don’t wake up and run through the reasons that this [robo-umpires] is such a terrible idea,” he replied. He later told me, “This is part of a movement to use algorithms to take the hard choices of living out of life.” Perhaps he’s right. We watch baseball to kill time, not to maximize it. Some players I have met take a dissenting stance toward the robots too, believing that accuracy is not the answer. According to Joe Russo, who plays for a New Jersey team, “With technology, people just want everything to be perfect. That’s not reality. I think perfect would be weird. Your teams are always winning, work is always just great, there’s always money in your pocket, your car never breaks down. What is there to talk about?”

*strike: a strike is when the batter swings at a ball and misses or when the batter does not swing at a ball that passes through the strike zone.

Time’s up

ANSWERS

1. tail

2. flippers

3. hair

4. seagrasses

5. lips

6. buoyancy

7. TRUE

8. NOT GIVEN

9. FALSE

10. NOT GIVEN

11. TRUE

12. NOT GIVEN

13. TRUE

14. B

15. F

16. B

17. laziness

18. anxious

19. threats

20. exams

21. perfectionists

22. guilt

23. A

24. C

25. A

26. E

27. NO

28. YES

29. NOT GIVEN

30. NO

31. NOT GIVEN

32. YES

33. former roles

34. subjective assessment

35. perceived area

36. numerous disputes

37. total silence

38. B

39. D

40. C

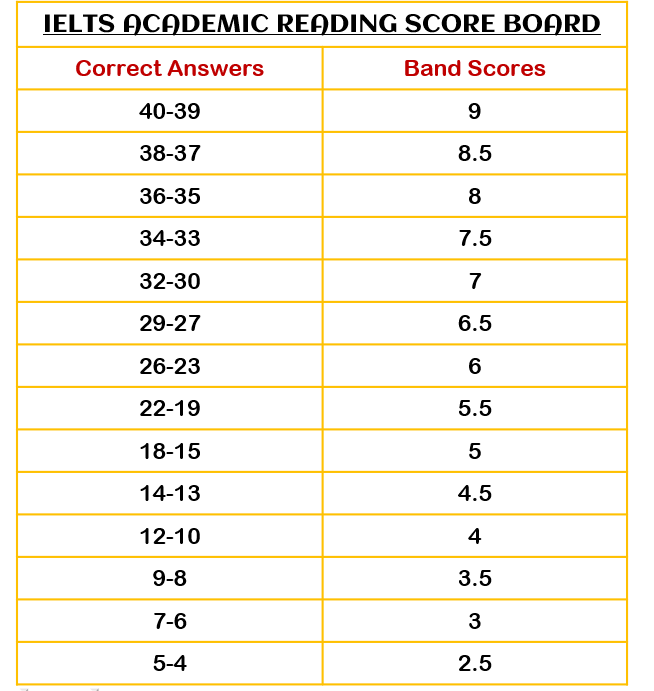

Y it is mistake if i write Hairs ?